The Serum Run

During the 1925 serum run to Nome, also known as the "Great Race of Mercy", 20 mushers and about 150 sled dogs relayed diphtheria antitoxin 674 miles (1,085 km) by dog sled across the U.S. territory of Alaska in a record-breaking five and a half days, saving the small city of Nome and the surrounding communities from an incipient epidemic. Both the mushers and their dogs were portrayed as heroes in the newly popular medium of radio, and received headline coverage in newspapers across the United States. Balto, the lead sled dog on the final stretch into Nome, became the most famous canine celebrity of the era after Rin Tin Tin, and his statue is a popular tourist attractions in New York City's Central Park. The publicity also helped spur an inoculation campaign in the U.S. that dramatically reduced the threat of the disease.

The sled dog was the primary means of transportation and communication in subarctic communities around the world, and the race became both the last great hurrah and the most famous event in the history of mushing, before first aircraft in the 1930s and then the snowmobile in the 1960s drove the dog sled almost into extinction. The resurgence of recreational mushing in Alaska since the 1970s is a direct result of the tremendous popularity of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, which honors the history of dog mushing with many traditions that commemorate the serum run.

Icebound

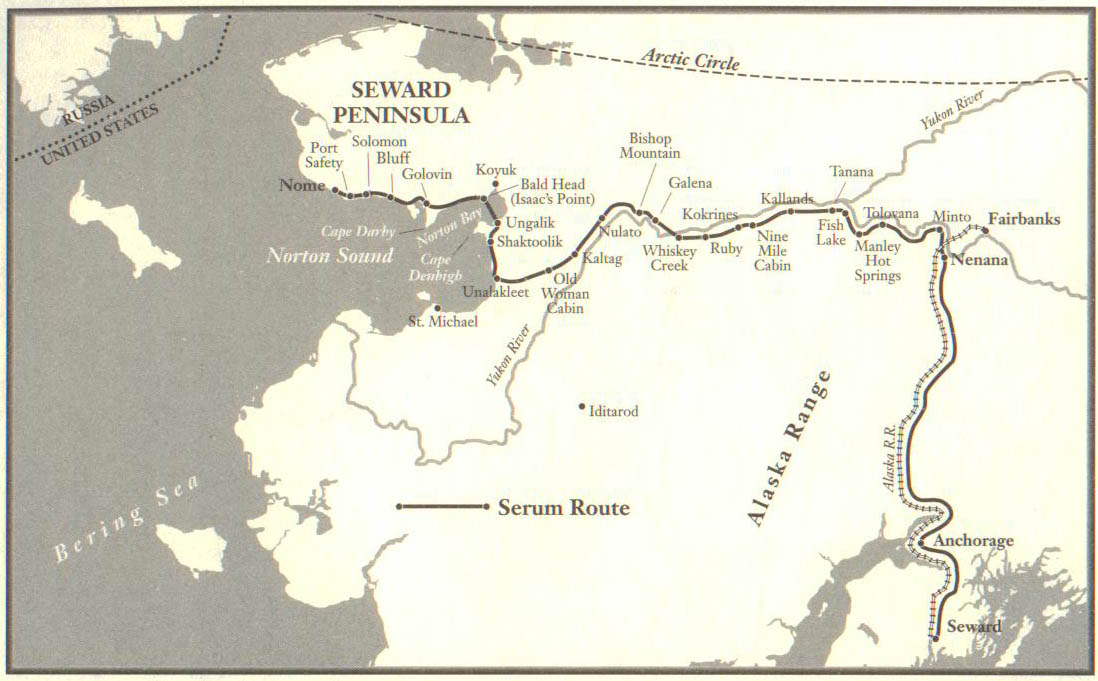

Nome lies just two degrees south of the Arctic Circle, and while greatly diminished from its peak of 20,000 during the gold rush days at the turn of the 20th century, it was still the largest town in the northern half of Alaska in 1925 with 455 Alaska Native and 975 settlers of European descent. (Salisbury & Salisbury 2003, p. 16) From November to July, the port on the southern shore of the Seward Peninsula of the Bering Sea was icebound and inaccessible by steamship, and the days shortened with the onset of the polar night. The only link to the rest of the world during the winter was the Iditarod Trail, which ran 938 miles (1,510 km) from the port of Seward in the south, across several mountain ranges and the vast Alaska Interior before reaching Nome. While within a decade bush pilots would become the dominant method of transportation during the winter months, the primary source of mail and needed supplies in 1925 was the dog sled.

Mail from the "Outside" (outside the Alaska Territory) was transported 420 miles (680 km) by train from the icefree port of Seward to Nenana, and then was transported the 674 miles (1,085 km) from Nenana to Nome by dog sled, which normally took 25 days.

Epidemic

The only doctor in Nome and the surrounding communities was Curtis Welch, who was supported by four nurses at the 24-bed Maynard Columbus Hospital. In the summer of 1924, his supply of 8,000 units of diphtheria antitoxin (from 1918) expired, but the order he placed with the health commissioner in Juneau did not arrive before the port closed.

Shortly after the departure of the last ship of the year, the Alameda, a two-year-old Alaska Native from the nearby village of Holy Cross became the first to display symptoms of diphtheria. Welch diagnosed it as tonsillitis, dismissing diphtheria because no one else in the child's family or village showed signs of the disease, which is extremely contagious and can survive for weeks outside the body. The child died the next morning, and an abnormally large number of cases of tonsillitis were diagnosed through December, including another fatality on December 28, which is rare. The child's mother refused to allow an autopsy. Two more Alaska Native children died, and on January 20 the first case of diphtheria was diagnosed in three-year-old Bill Barnett, who had the characteristic grayish lesions on his throat and in his nasal membranes. Welch did not administer the antitoxin, because he was worried the expired batch might weaken the boy, who died the next day.

On January 21, seven-year-old Bessie Stanley was diagnosed in the late stages of the disease, and was injected with 6,000 units of antitoxin. She died later that day. The same evening, Welch called Mayor George Maynard, and arranged an emergency town council meeting. Welch announced he needed at least one million units to stave off an epidemic. The council immediately implemented a quarantine, and Emily Morgan was appointed Quarantine Nurse.

On January 22, 1925, Welch sent a radio telegram via the U.S. Army Signal Corps and alerted all major towns in Alaska including the governor in Juneau of the public health risk. A second to the U.S. Public Health Service in Washington, D.C. read:

| “ |

An epidemic of diphtheria is almost inevitable here STOP I am in urgent need of one million units of diphtheria antitoxin STOP Mail is only form of transportation STOP I have made application to Commissioner of Health of the Territories for antitoxin already STOP There are about 3000 white natives in the district |

” |

|

| ||

By January 24 there were two more fatalities, and Welch and Morgan diagnosed 20 more confirmed cases, and 50 more at risk. The number of people threatened in the area of northwest Alaska centered around Nome was about 10,000, and the expected mortality rate was close to 100 percent without the antitoxin. A previous influenza epidemic (Spanish flu) across the Seward Peninsula in 1918 and 1919 wiped out about 50 percent of the native population of Nome, and 8 percent of the native population of Alaska. More than 1,000 people died in northwest Alaska, and double that across the state, and the majority were Alaska Natives. The Native Americans had no resistance to either of these diseases.

Wings versus paws

At the January 24 meeting of the board of health superintendent Mark Summers of the Hammon Consolidated Gold Fields proposed a dogsled relay, using two fast teams. One would start at Nenana and the other at Nome, and they would meet at Nulato. His employee, the Norwegian Leonhard Seppala, was the obvious and only choice for the 630-mile (1,014 km) round trip from Nome to Nulato and back. He had previously made the run from Nome to Nulato in a record-breaking four days, won the All-Alaska Sweepstakes three times, and had become something of a legend for his athletic ability and rapport with his Siberian huskies. His lead dog Togo was equally famous for his leadership, intelligence, and ability to sense danger.

Mayor Maynard proposed flying the antitoxin by aircraft. In February 1924, the first winter aircraft flight in Alaska had been conducted between Fairbanks and McGrath by Carl Eielson, who flew a reliable De Havilland DH-4 issued by the U.S. Post Office on 8 experimental trips. The longest flight was only 260 miles (420 km), the worst conditions were −10 °F (−23.3 °C) which required so much winter clothing that the plane was almost unflyable, and the plane made several crash landings.

The only planes operating in Alaska in 1925 were three World War I vintage Standard J-1 biplanes belonging to Bennet Rodebaugh's Fairbanks Airplane company (later Wien Air Alaska) The aircraft were dismantled for the winter, had open cockpits, and had water-cooled engines that were unreliable in cold weather. Since both pilots were in the continental United States, Alaska Delegate Dan Sutherland attempted to get the authorization to use an inexperienced pilot, Roy Darling.

While potentially quicker, the board of health rejected the option and voted unanimously for the dogsled relay. Seppala was notified that evening and immediately began to train.

The U.S. Public Health Service had located 1.1 million units of serum in West Coast hospitals which could be shipped to Seattle, and then transported to Alaska. The Alameda would be the next ship north, and would not arrive in Seattle until January 31, and then would take another 6 to 7 days to arrive in Seward. On January 26, 300,000 units were discovered in Anchorage Railroad Hospital, when the chief of surgery, John Beeson, heard of the need. At Governor Bone's order, it was packed and handed to conductor Frank Knight, who arrived in Nenana on January 27. While not sufficient to defeat the epidemic, the 300,000 units could hold it at bay until the larger shipment arrived.

The temperatures across the Interior were at 20-year lows due to a high pressure system from the Arctic, and in Fairbanks the temperature was −50 °F (−45.6 °C). A second system was burying the Panhandle, as 25 mph (40 km/h) winds swept snow into 10-foot (3.05 m) drifts. Travel by sea was hazardous, and across the Interior most forms of transportation shut down. In addition, there were limited hours of daylight to fly, due to the polar night.

While the first batch of serum was traveling to Nenana, Governor Scott Bone gave final authorization to the dog relay, but ordered Edward Wetzler, the U.S. Post Office inspector, to arrange a relay of the best drivers and dogs across the Interior. The teams would travel day and night until they handed off the package to Seppala at Nulato.

The decision outraged William Fendtriss "Wrong Font" Thompson, publisher of the Daily Fairbanks News-Miner and aircraft advocate, who helped line up the pilot and plane. He used his paper to write scathing editorials.

The mail route from Nenana to Nome crossed the barren Alaska Interior, following the Tanana River for 137 miles (220 km) to the village Tanana at the junction with the Yukon River, and then following the Yukon for 230 miles (370 km) to Kaltag. The route then passed west 90 miles (140 km) over the Kaltag Portage and the forests and plateaus of the Kuskokwim Mountains to Unalakleet on the shore of Norton Sound. The route then continued for 208 miles (335 km) northwest around the southern shore of the Seward Peninsula with no protection from gales and blizzards, including a 42 miles (68 km) stretch across the shifting ice of the Bering Sea. In total, 674 miles (1,085 km).

Wetzler contacted Tom Parson, an agent of the Northern Commercial Company, which contracted to deliver mail between Fairbanks and Unalakleet. Telephone and telegrams turned the drivers back to their assigned roadhouses. The mail carriers held a revered position in the territory, and were the best dog punchers in Alaska. The majority of relay drivers across the Interior were native Athabaskans, direct descendants of the original dog mushers.

The first musher in the relay was "Wild Bill" Shannon, who was handed the 20 pounds (9.1 kg) package at the train station in Nenana on January 27 at 9:00 PM AKST by night. Despite a temperature of −50 °F (−45.6 °C), Shannon left immediately with his team of 9 inexperienced dogs, led by Blackie. The temperature began to drop, and the team was forced onto the colder ice of the river because the trail had been destroyed by horses. Despite jogging alongside the sled to keep warm, Shannon developed hypothermia. He reached Minto at 3 AM, with parts of his face black from frostbite. The temperature was −62 °F (−52.2 °C). After warming the serum by the fire and resting for four hours, Shannon dropped three dogs and left with the remaining 6. The three dogs died shortly after Shannon returned for them, and a fourth may have perished as well.

Half-Athabaskan Edgar Kallands arrived in Minto the night before, and was sent back to Tolovana, traveling 70 mi (110 km) the day before the relay. Shannon and his team arrived in bad shape at 11 AM, and handed over the serum. After warming the serum in the roadhouse, Kallands headed into the forest. The temperature had risen to −56 °F (−48.9 °C), and according to at least one report the owner of the roadhouse at Manley Hot Springs had to pour hot water over Kallands' hands to get them off the sled's handlebar when he arrived at 4 PM.

No new cases of diphtheria were diagnosed on January 28, but two new cases were diagnosed on January 29. The quarantine had been obeyed but lack of diagnostic tools and the contagiousness of the strain rendered it ineffective. More units of serum were discovered around Juneau the same day. While no count exists, the estimate based on weight is roughly 125,000 units, enough to treat 4 to 6 patients. The crisis had become headline news in newspapers, including San Francisco, Cleveland, Washington D.C., and New York, and spread to the radio sets which were just becoming common. The storm system from Alaska hit the continental United States, bringing record lows to New York, and freezing the Hudson River.

A fifth death occurred on January 30. Maynard and Sutherland renewed their campaign for flying the remaining serum by plane. Different proposals included flying a large aircraft 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from Seattle to Nome, carrying a plane to the edge of the pack ice via Navy ship and launching it, and the original plan of flying the serum from Fairbanks. Despite receiving headline coverage across the country, the support of several cabinet departments, and from Arctic explorer Roald Amundsen, the plans were rejected by experienced pilots, the Navy, and Governor Bone. Thompson's paper again became virulent.

In response, Bone decided to speed up the relay and authorized the addition of more drivers to Seppala's leg of the relay, so they could travel without rest. Seppala was still scheduled to cover the most dangerous leg, the shortcut across Norton Sound, but the telephone and telegraph systems bypassed the small villages he was passing through, and there was no way to tell him to wait at Shaktoolik. The plan relied on the driver from the north catching Seppala on the trail. Summers arranged for drivers along the last leg, including Seppala's colleague Gunnar Kaasen.

From Manley Hot Springs, the serum passed through largely Athabascan hands before George Nollner delivered it to Charlie Evans at Bishop Mountain on January 30 at 3 AM. The temperature had warmed slightly, but at −62 °F (−52.2 °C) was dropping again. Evans relied on his lead dogs when he passed through ice fog where the Koyukuk River had broken through and surged over the ice, but forgot to protect the groins of his two short-haired mixed breed lead dogs with rabbit skins. Both dogs collapsed with frostbite, Evans may have had to lead the team the remaining distance to Nulato himself. He arrived at 10 AM; both dogs were dead. Tommy Patsy departed within half an hour.

The serum then crossed the Kaltag Portage in the hands of "Jackscrew" and the Alaska Native Victor Anagick, who handed it to his fellow Alaska Native Myles Gonangnan on the shores of the Sound, at Unalakleet on January 31 at 5 AM. Gonangan saw the signs of a storm brewing, and decided not to take the shortcut across the dangerous ice of the Sound. He departed at 5:30 AM, and as he crossed the hills, "the eddies of drifting, swirling snow passing between the dog's legs and under the bellies made them appear to be fording a fast running river." (Salisbury & Salisbury 2003, p. 203) The whiteout conditions cleared as he reached the shore, and the gale-force winds drove the wind chill to −70 °F (−56.7 °C). At 3 PM he arrived at Shaktoolik. Seppala was not there, but Henry Ivanoff was waiting just in case.

On January 30, the number of cases in Nome had reached 27 and the antitoxin was depleted. According to a reporter living in Nome, "All hope is in the dogs and their heroic drivers... Nome appears to be a deserted city." (Salisbury & Salisbury 2003, p. 205) With the report of Gonangan's progress on January 31, Welch believed the serum would arrive the next day.

Leonhard Seppala and his dog sled team, with his lead dog Togo, traveled 91 miles (146 km) from Nome from January 27 to January 31 into the oncoming storm. They took the shortcut across the Norton Sound, and headed toward Shaktoolik. The temperature in Nome was a relatively warm −20 °F (−28.9 °C), but in Shaktoolik the temperature was estimated at −30 °F (−34.4 °C), and the gale force winds causing a wind chill of −85 °F (−65.0 °C).

Henry Ivanoff's team ran into a reindeer and got tangled up just outside of Shaktoolik. Seppala still believed he had more than 100 miles (160 km) to go and was racing to get off the Norton Sound before the storm hit. He was passing the team when Ivanoff shouted, "The serum! The serum! I have it here!" (Salisbury, 2003, page 207)

With the news of the worsening epidemic, Seppala decided to brave the storm and once again set out across the exposed open ice of the Norton Sound when he reached Ungalik, after dark. The temperature was estimated at −30 °F (−34.4 °C), but the wind chill with the gale force winds was −85 °F (−65.0 °C). Togo led the team in a straight line through the dark, and they arrived at the roadhouse in Isaac's Point on the other side at 8 PM. In one day, they had traveled 84 mi (135 km), averaging 8 mph (13 km/h). The team rested, and departed at 2 AM into the full power of the storm.

During the night the temperature dropped to −40 °F (−40.0 °C), and the wind increased to storm force (at least 65 mph (105 km/h). The team ran across the ice, which was breaking up, while following the shoreline. They returned to shore to cross Little McKinley Mountain, climbing 5,000 feet (1,500 m). After descending to the next roadhouse in Golovin, Seppala passed the serum to Charlie Olsen on February 1 at 3 PM.

On February 1, the number of cases rose to 28. The serum en route was sufficient to treat 30 people. With the powerful blizzard raging and winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), Welch ordered a stop to the relay until the storm passed, reasoning that a delay was better than the risk of losing it all. Messages were left at Solomon and Point Safety before the lines went dead.

Olsen was blown off the trail, and suffered severe frostbite in his hands while putting blankets on his dogs. The wind chill was −70 °F (−56.7 °C). He arrived at Bluff on February 1 at 7 PM in poor shape. Gunnar Kaasen waited until 10 PM for the storm to break, but it only got worse and the drifts would soon block the trail so he departed into a headwind.

Kaasen traveled through the night, through drifts, and river overflow over the 600-foot (183 m) Topkok Mountain. Balto led the team through visibility so poor that Kaasen could not always see the dogs harnessed closest to the sled. He was two miles (3 km) past Solomon before he realized it, and kept going. The winds after Solomon were so severe that his sled flipped over and he almost lost the cylinder containing the serum when it fell off and became buried in the snow. He acquired frostbite when he had to use his bare hands to feel for the cylinder.

Kaasen reached Point Safety ahead of schedule on February 2, at 3 AM. Ed Rohn believed that Kaasen and the relay was halted at Solomon, so he was sleeping. Since the weather was improving, it would take time to prepare Rohn's team, and Balto and the other dogs were moving well, Kaasen pressed on the remaining 25 miles (40 km) to Nome, reaching Front Street at 5:30 AM. Not a single ampule was broken, and the antitoxin was thawed and ready by noon.

Together, the teams covered the 674 miles (1,085 km) in 127 and a half hours, which was considered a world record, incredibly done in extreme subzero temperatures in near-blizzard conditions and hurricane-force winds. Some dogs froze to death during the trip.

Second relay

Margaret Curran from the Solomon roadhouse was infected, which raised fears that the disease might spread from patrons of the roadhouse to other communities. The 1.1 million units had left Seattle on January 31, and was not due by dog sled until February 8. Welch asked for half the serum to be delivered by aircraft from Fairbanks. Contacted Thompson and Sutherland, and Darling made a test flight the next morning. With his health advisor, Governor Bone concluded the cases in Nome were actually going down, and withheld permission, but preparations went ahead. The U.S. Navy moved a minesweeper north from Seattle, and the Signal Corps were ordered to light fires to guide the planes.

By February 3, the original 300,000 units had proved to be still effective, and the epidemic was under control. A sixth death, probably unrelated to diphtheria, was widely reported as a new outbreak of the disease. The batch from Seattle arrived on board the Admiral Watson on February 7. Acceding to pressure, Governor Bone authorized half to be delivered by plane. On February 8 the first half of the second shipment began its trip by dog sled, while the plane failed to start when a broken radiator shutter caused the engine to overheat. The plane failed the next day as well, and the mission was scrapped. Thompson was gracious in his editorials.

The second relay included many of the same drivers, and also faced harsh conditions. The serum arrived on February 15.

Aftermath

The death toll is officially listed as either 5, 6, or 7, but Welch later estimated there were probably at least 100 additional cases among "the Eskimo camps outside the city. The Natives have a habit of burying their children without reporting the death." Forty-three new cases were diagnosed in 1926, but they were easily managed with the fresh supply of serum. (Salisbury, 2003, footnotes on page 235 and 243)

All participants received letters of commendation from President Calvin Coolidge, and the Senate stopped work to recognize the event. Each musher during the first relay received a gold medal from the H. K. Mulford company, and the territory awarded them each USD $25. Poems and letters from children poured in, and spontaneous fund raising campaigns sprang up around the country.

Gunnar Kaasen and his team became celebrities and toured the West Coast from February 1925 to February 1926, and even starred in a 30-minute film entitled Balto's Race to Nome. A statue of Balto by Frederick Roth was unveiled New York City's Central Park during a visit on December 15, 1925. Balto and the other dogs became part of a sideshow and lived in horrible conditions until they were rescued by George Kimble and fund raising campaign by the children of Cleveland, Ohio. On March 19, 1927, Balto received a hero's welcome as they arrived at their permanent home at the Cleveland Zoo. Because of age, Balto was euthanised on March 14, 1933 He was mounted and placed on display in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

But many mushers today consider Seppala and Togo to be the true heroes of the run as together they covered the longest and most hazardous leg. They made a round trip of 261 miles (420 km) from Nome to Shaktoolik and back to Golovin, and delivered the serum a total of 91 miles (146 km), almost double the distance of any other team. After Kaasen's return, he was accused of being a glory hog. Seppala became upset when the media attributed Togo's achievements to Balto, and commented, "it was almost more than I could bear when the 'newspaper dog' Balto received a statue for his 'glorious achievements.'" (Salisbury & Salisbury 2003, p. 248)

In October 1926, Seppala took Togo and his team on a tour from Seattle to California, and then across the Midwest to New England, and consistently drew huge crowds. They were featured at Madison Square Garden in New York City for 10 days, and Togo received a gold medal from Roald Amundsen. In New England Seppala's team of Siberian huskies ran in many races, easily defeating the local Chinooks. Seppala sold most of his team to a kennel in Poland Spring, Maine and most huskies in the U.S. can trace their descent from one of these dogs. Seppala visited Togo, until he was euthanised on December 5, 1929. After his death, Seppala had Togo preserved and mounted, and today the dog is on display in a glass case at the Iditarod museum in Wasilla, Alaska.

None of the other mushers received the same degree of attention, though Wild Bill Shannon briefly toured with Blackie. The media largely ignored the Athabaskan and Alaska Native mushers, who covered two-thirds the distance to Nome. According to Edgard Kallands, "it was just an every day occurrence as far as we were concerned." (Salisbury & Salisbury 2003, p. 255)

The serum race helped the Kelly Act, which was signed into law on February 2. The bill allowed private aviation companies to bid on mail delivery contracts. Technology improved and in a decade, air mail routes were established in Alaska. The last private dog sled to deliver mail under contract took place in 1938, and the last U.S. Post Office dog sled route closed in 1963. Dog sledding remained in the rural Interior but became nearly extinct when snowmobiles spread in the 1960s. Mushing was revitalized as a recreational sport in the 1970s with the immense popularity of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race.

While the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, which runs more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) across from Anchorage to Nome, is actually based on the All-Alaska Sweepstakes, it has many traditions which commemorate the race, and especially Seppala and Togo. The honorary musher for the first seven races was Leonhard Seppala. Other serum run participants, including "Wild Bill" Shannon, Edgar Kallands, Bill McCarty, Charlie Evans, Edgar Nollner, Harry Pitka, and Henry Ivanoff have also been honored. The 2005 Iditarod honored Jirdes Winther Baxter, the last known survivor of the epidemic. The position is now known as Leonhard Seppala's Honorary Musher, and the Leonhard Seppala Humanitarian Award is given to the musher who provides the best dog care while still remaining competitive, and the Leonhard Seppala Heritage Grant is an Iditarod scholarship. The two races follow the same route from Ruby to Nome.

A reenactment of the serum run was held in 1975, which took 6 days longer than the 1925 serum run. Many of the participants were descendants of the original 20. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan sent a letter of recognition to Charlie Evans, Edgar Nollner, and Bill McCarty, the only remaining survivors. Nollner was the last to die, on January 18, 1999 of a heart attack.

Controversy

There is much controversy surrounding Balto's role in this race and the statue in Central Park. According to Leonhard Seppala, Togo's musher, Balto was a scrub freight dog that was left behind when he set out on the trip. Seppala was sent out on what he thought was a solo run to meet the train at Nenana. After he and his dogs were on the trail it was decided to send out other mushers in a relay. Seppala ran over 170 miles (270 km) across some of the most dangerous and treacherous parts of the run. He met the serum runner, took the hand off and returned another 91 miles (146 km), having run over 261 miles (420 km) in total. He then handed the serum off to Charlie Olson. Charlie carried it 25 miles (40 km) to Bluff where he turned it over to Gunnar Kaasen. Kaasen was supposed to hand-off the serum to Rohn at Port Safety, but Rohn had gone to sleep and Kaasen decided to keep going to Nome. In all, Kaasen and Balto ran a total of 53 miles (85 km) and many thought his decision to not wake Rohn was motivated by a desire to grab the glory for himself and Balto.

The actual statue of Balto was modeled after Balto, but shows him wearing Togo's colors (awards). In the last years of his life Seppala was heartbroken by the way the credit had gone to Balto; in his mind Togo was the real hero of the serum race.

Relay participants and distances

Mushers (in order) and the distance they covered included: (Salisbury & Salisbury 2003, p. 263)

| Start | Musher | Leg | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| January 27 | "Wild" Bill Shannon | Nenana to Tolovana | 52 mi (84 km) |

| January 28 | Edgar Kallands | Tolovana to Manley Hot Springs | 31 mi (50 km) |

| Dan Green | Manley Hot Springs to Fish Lake | 28 mi (45 km) | |

| Johnny Folger | Fish Lake to Tanana | 26 mi (42 km) | |

| January 29 | Sam Joseph | Tanana to Kallands | 34 mi (55 km) |

| Titus Nikolai | Kallands to Nine Mile Cabin | 24 mi (39 km) | |

| Dan Corning | Nine Mile Cabin to Kokrines | 30 mi (48 km) | |

| Harry Pitka | Kokrines to Ruby | 30 mi (48 km) | |

| Bill McCarty | Ruby to Whiskey Creek | 28 mi (45 km) | |

| Edgar Nollner | Whiskey Creek to Galena | 24 mi (39 km) | |

| January 30 | George Nollner | Galena to Bishop Mountain | 18 mi (29 km) |

| Charlie Evans | Bishop Mountain to Nulato | 30 mi (48 km) | |

| Tommy Patsy | Nulato to Kaltag | 36 mi (58 km) | |

| Jackscrew | Kaltag to Old Woman Shelter | 40 mi (64 km) | |

| Victor Anagick | Old Woman Shelter to Unalakleet | 34 mi (55 km) | |

| January 31 | Myles Gonangnan | Unalakleet to Shaktoolik | 40 mi (64 km) |

| Henry Ivanoff | Shaktoolik to just outside Shaktoolik | 0 mi (0 km) | |

| Leonhard Seppala | Just outside Shaktoolik to Golovin | 91 mi (146 km) | |

| February 1 | Charlie Olson | Golovin to Bluff | 25 mi (40 km) |

| Gunnar Kaasen | Bluff to Nome | 53 mi (85 km) |

Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, usually just called the Iditarod, is an annual sled dog race in Alaska, where mushers and teams of typically 16 dogs cover 1,161 miles (1,868 km) in eight to fifteen days from Willow (near Anchorage) to Nome. The Iditarod began in 1973 as an event to test the best sled dog mushers and teams, evolving into the highly competitive race it is today. The current fastest winning time record was set in 2002 by Martin Buser with a time of 8 days, 22 hours, 46 minutes, and 2 seconds.[1][clarification needed]

Teams frequently race through blizzards causing whiteout conditions, and sub-zero weather and gale-force winds which can cause the wind chill to reach −100 °F (−73.3 °C). The trail runs through the U.S. state of Alaska. A ceremonial start occurs in the city of Anchorage and is followed by the official restart in Willow, a city in the south central region of the state. The restart was originally in Wasilla, but due to too little snow, the restart was permanently moved to Willow in 2008.[2] The trail proceeds from Willow up the Rainy Pass of the Alaska Range into the sparsely populated interior, and then along the shore of the Bering Sea, finally reaching Nome in western Alaska. The teams cross a harsh landscape under the canopy of the Northern Lights, through tundra and spruce forests, over hills and mountain passes, and across rivers. While the start in Anchorage is in the middle of a large urban center, most of the route passes through widely separated towns and villages, and small Athabaskan and Inupiaq settlements. The Iditarod is regarded as a symbolic link to the early history of the state, and is connected to many traditions commemorating the legacy of dog mushing. Each year the trails switch; every even year they take the north trail and odd years they take the south trail.

The race is the most popular sporting event in Alaska, and the top mushers and their teams of dogs are local celebrities; this popularity is credited with the resurgence of recreational mushing in the state since the 1970s. While the yearly field of more than fifty mushers and about a thousand dogs is still largely Alaskan, competitors from fourteen countries have completed the event including the Swiss Martin Buser, who became the first international winner in 1992.

The Iditarod received more attention outside of the state after the 1985 victory of Libby Riddles, a long shot who became the first woman to win the race. Susan Butcher became the second woman to win the race, and went on to dominate for half a decade. Print and television journalists and crowds of spectators attend the ceremonial start at the intersection of Fourth Avenue and D Streets in Anchorage, and in smaller numbers at the checkpoints along the trail.

History

Portions of the Iditarod Trail were used by the Native American Inupiaq and Athabaskan peoples hundreds of years before the arrival of Russian fur traders in the 1800s, but the trail reached its peak between the late 1880s and the mid 1920s as miners arrived to dig coal and later gold, especially after the Alaska gold rushes at Nome in 1898, and at the "Inland Empire" along the Kuskokwim Mountains between the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers, in 1908.

The primary communication and transportation link to the rest of the world during the summer was the steamship; but between October and June the northern ports like Nome became icebound, and dog sleds delivered mail, firewood, mining equipment, gold ore, food, furs, and other needed supplies between the trading posts and settlements across the Interior and along the western coast. Roadhouses where travelers could spend the night sprang up every 14 to 30 miles (23 to 48 km) until the end of the 1920s, when the mail carriers were replaced by bush pilots flying small aircraft and the roadhouses vanished. Dog sledding persisted in the rural parts of Alaska, but was almost driven into extinction by the spread of snowmobiles in the 1960s.

During its heyday, mushing was also a popular sport during the winter, when mining towns shut down. The first major competition was the tremendously popular 1908 All-Alaska Sweepstakes (AAS), which was started by Allan "Scotty" Alexander Allan, and ran 408 miles (657 km) from Nome to Candle and back. The event introduced the first Siberian huskies to Alaska in 1910, where they quickly became the favored racing dog, replacing the Alaskan malamute and mongrels bred from imported huskies and other large breeds, like setters and pointers. In 1914, the Norwegian immigrant Leonhard Seppala first appeared, and went on to win the race in 1915, 1916, and 1917, before the race was discontinued in 1918 during World War I.

The most famous event in the history of Alaskan mushing is the 1925 serum run to Nome, also known as the "Great Race of Mercy." A diphtheria epidemic threatened Nome, especially the Inuit children who had no immunity to the "white man's disease," and the nearest quantity of antitoxin was found to be in Anchorage. Since the two available planes were both dismantled and had never been flown in the winter, Governor Scott Bone approved a safer route. The 20-pound (9.1 kg) cylinder of serum was sent by train 298 miles (480 km) from the southern port of Seward to Nenana, where it was passed just before midnight on January 27 to the first of twenty mushers and more than 100 dogs who relayed the package 674 miles (1,085 km) from Nenana to Nome. The dogs ran in relays, with no dog running over 100 miles (160 km).

The Norwegian Gunnar Kaasen and his lead dog Balto arrived on Front Street in Nome on February 2 at 5:30 a.m., just five and a half days later. The two became media celebrities, and a statue of Balto was erected in Central Park in New York City in 1925, where it has become one of the most popular tourist attractions. However, most mushers consider Leonhard Seppala and his lead dog Togo to be the true heroes of the run. Together they covered the most hazardous stretch of the route, and carried the serum farther than any other team.

The Centennial Race, along portions of the Iditarod Trail, was the brainchild of Dorothy G. Page, who wanted to sponsor a sled dog race to honor mushers. With the support of Joe Redington Sr. (named the "Father of the Iditarod" by one of the local newspapers), the first race (then known as the Iditarod Trail Seppala Memorial Race in honor of Leonhard Seppala) was held in 1967 and covered 25 miles (40 km) near Anchorage. The purse of USD $25,000 attracted a field of 58 racers, and the winner was Isaac Okleasik. The next race, in 1968, was canceled for lack of snow, and the small $1,000 purse in 1969 only drew 12 mushers.

Redington along with two school teachers, Gleo Huyck and Tom Johnson was the impetus behind extending the race more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) along the historic route to Nome. The three co-founders of the race started in October 1972 to plan the now famous race. A major fundraising campaign which raised a purse of $51,000 was also started at the same time. This race was the first true Iditarod Race and was held in 1973, and attracted a field of 34 mushers, 22 of whom completed the race. Dorothy Page had nothing to do with the 1973 race, stating that she "washes her hands of the event". The event was a success; even though the purse dropped in the 1974 race, the popularity caused the field of mushers to rise to 44, and corporate sponsorship in 1975 put the race on secure financial footing. Despite the loss of sponsors during a dog abuse scandal in 1976, the Iditarod caused a resurgence of recreational mushing in the 1970s, and has continued to grow until it is now the largest sporting event in the state. While the race was originally patterned after the All Alaska Sweepstakes, the Iditarod Trail Committee promotes it as a commemoration of the serum delivery.

The race's namesake is the Iditarod Trail, which was designated as one of the first four National Historic Trails in 1978. The trail in turn is named for the town of Iditarod, which was an Athabaskan village before becoming the center of the Inland Empire's Iditarod Mining District in 1910, and then turning into a ghost town at the end of the local gold rush. The name Iditarod may be derived from the Athabaskan haiditarod, meaning "far distant place".

The main route of the Iditarod trail extends 938 miles (1,510 km) from Seward in the south to Nome in the northwest, and was first surveyed by Walter Goodwin in 1908, and then cleared and marked by the Alaska Road Commission in 1910 and 1911. The entire network of branching paths covers a total of 2,450 miles (3,940 km). Except for the start in Anchorage, the modern race follows parts of the historic trail.

Route

This route is a grueling one. While always longer than 1,000 miles (1,600 km), the trail is actually composed of a northern route, which is run on even-numbered years, and a southern route, which is run on odd-numbered years. Both follow the same trail for 444 miles (715 km), from Anchorage to Ophir, where they diverge and then rejoin at Kaltag, 441 miles (710 km) from Nome. The race used the northern route until 1977, when the southern route was added to distribute the impact of the event on the small villages in the area, none of which have more than a few hundred inhabitants. Passing through the historic town of Iditarod was a secondary benefit.

Aside from the addition of the southern route, the route has remained relatively constant. The largest changes were the addition of the restart location in 1975, and the shift from Ptarmigan to Rainy Pass in 1976. Checkpoints along the route are also occasionally added or dropped, and the ceremonial start of the route and the restart point are commonly adjusted due to weather.

As a result the exact measured distance of the race varies, but according to the official website the northern route is 1,112 miles (1,790 km) long, and the southern route is 1,131 miles (1,820 km) long (ITC, Southern & Northern). The length of the race is also frequently rounded to either 1,050, 1,100, or 1,150 miles (1690, 1770 or 1850 km), but is officially set at 1,049 miles (1688 km), which honors Alaska's status as the 49th state.

Checkpoints

There are currently 25 checkpoints on the northern route and 26 on the southern route where mushers must sign in. Some mushers prefer to camp on the trail and immediately press on, but others stay and rest. Mushers purchase supplies and equipment in Anchorage, which are flown ahead to each checkpoint by the Iditarod Air Force. The gear includes food, extra booties for the dogs, headlamps for night travel, batteries (for the lamps, music, or radios), tools and sled parts for repairs, and even lightweight sleds for the final dash to Nome. There are three mandatory rests that each team must take during the Iditarod: one 24-hour layover, to be taken at any checkpoint; one eight-hour layover, taken at any checkpoint on the Yukon River; and an eight-hour stop at White Mountain. Other than these three mandatory stops, the mushers may be racing their dogs.

In 1985, the race was suspended for the first time for safety reasons when weather prevented the Iditarod Air Force from delivering supplies to Rohn and Nikolai, the first two checkpoints in the Alaska Interior. Fifty-eight mushers and 508 dogs congregated at the small lodge in Rainy Pass for three days, while emergency shipments of food were flown in from Anchorage. Weather also halted the race later at McGrath, and the two stops added almost a week to the winning time.

Ceremonial start

The race starts on the first Saturday in March, at the first checkpoint on Fourth Avenue, in downtown Anchorage. A five-block section of the street is barricaded off as a staging area, and snow is stockpiled and shipped in by truck the night before to cover the route to the first checkpoint. Prior to 1983, the race started at Mulcahy Park.

Shortly before the race, a ribbon-cutting ceremony is held under the flags representing the home countries and states of all competitors in the race. The first musher to depart at 10:00 a.m. AST is an honorary musher, selected for their contributions to dog sledding. From the first race in 1973 until 1980, the honorary musher was Leonhard Seppala, who covered the longest distance in the 1925 diphtheria serum run. The first competitor leaves at 10:02, and the rest follow, separated by two-minute intervals. The start order is determined during a banquet held two days prior by letting the mushers choose their starting position. Selections are made in the order of musher registrations and mushers may choose any position that has not been previously chosen. The teams are helped to the starting line by several handlers and lined up at the starting line while the musher sets their brake in anticipation of the signal to start.

On the sled will also be an "Idita-Rider". The Idita-Riders purchase via auction in the preceding January the right to ride; the first auction was held entirely online for the first time in 2005. In 2005, the average bid was USD $1918.09, and raised a total of $140,021.00. This is an exciting portion of the race for dogs and musher, as it is one of the few portions of the race where there are spectators, and the only spot where the trail winds through an urban environment. However, In "Iditarod Dreams," DeeDee Jonrowe wrote, "A lot of mushers hate the Anchorage start. They don't like crowds. They worry that their dogs get too excited and jumpy."[3] The time for covering this portion of the race does not count toward the official race time per rule #55, so the dogs, musher, and Idita-Rider are free to take this all in at a relaxed pace. The mushers then continue through several miles of city streets and city trails before reaching the foothills to the east of Anchorage, in Chugach State Park in the Chugach Mountains. The teams then follow Glenn Highway for two to three hours until they reach Eagle River, 20 miles (32 km) away. Once they arrive at the Veterans of Foreign Wars building, the mushers check in, unharness their teams, return them to their boxes, and drive 30 miles (48 km) of highway to the restart point.

During the first two races in 1973 and 1974, the teams crossed the mudflats of Cook Inlet to Knik (the original restart location), but this was discontinued because the weather frequently hovers around freezing, turning it into a muddy hazard. The second checkpoint also occasionally changes due to weather; in 2005, the checkpoint was changed from Eagle River to Campbell Airstrip, only 11 miles (18 km) away.

Restart

| Restart |

|---|

| Willow to Yentna Station 14 mi (23 km) |

| Yentna Station to Skwentna 34 mi (55 km) |

| Skwentna to Finger Lake 45 mi (72 km) |

| Finger Lake to Rainy Pass 30 mi (48 km) |

| Into the Interior |

After the dogs are shuttled to the third checkpoint, the race restarts the next day (Sunday) at 2:00 p.m. AST. Prior to 2004, the race was restarted at 10:00 a.m., but the time has been moved back so the dogs will be starting in colder weather, and the first mushers arrive at Skwentna well after dark, which reduces the crowds of fans who fly into the checkpoint.

The traditional restart location was the headquarters of the Iditarod Trail Committee, in Wasilla, but in 2008 the official restart was pushed further north to Willow Lake. In 2003 it was bumped 300 miles (480 km) north to Fairbanks due to warm weather and poor trail conditions. The mushers depart, separated by the same intervals as their arrival at the second checkpoint.

The first 100 miles (160 km) from Willow through the checkpoints at Yentna Station Station to Skwentna are known as "moose alley". The many moose in the area find it difficult to move and forage for food when the ground is thick with snow. As a result, the moose sometimes prefer to use pre-existing trails, causing hazards for the dog teams. In 1985, Susan Butcher lost her chance at becoming the first woman to win the Iditarod when her team made a sharp turn, and encountered a pregnant moose. The moose killed two dogs and seriously injured six more in the twenty minutes before Duane "Dewey" Halverson arrived and shot the moose. In 1982, Dick Mackey, Warner Vent, Jerry Austin, and their teams were driven into the forest by a charging moose.

Otherwise, the route to Skwentna is easy, over flat lowlands, and well marked by stakes or tripods with reflectors or flags. Most mushers push through the night, and the first teams usually arrive at Skwentna before dawn. Skwentna is a 40-minute hop from Anchorage by air, and dozens of planes land on the airstrip or on the Skwentna River, bringing journalists, photographers, and spectators.

From Skwentna, the route follows the Skwentna River into the southern part of the Alaska Range to Finger Lake. The stretch from Finger Lake to Rainy Pass, on Puntilla Lake, becomes more difficult, as the teams follow the narrow Happy River Gorge, where the trail balances on the side of a heavily forested incline. Rainy Pass is the most dangerous check point in the Iditarod. In 1985, Jerry Austin broke a hand and two of his dogs were injured when the sled went out of control and hit a stand of trees. Many others have suffered from this dangerous checkpoint. Rainy Pass is part of the Historic Iditarod Trail, but until 1976 the pass was inaccessible and route detoured through Ptarmigan Pass, also known as Hellsgate, because of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake.

Into the Interior

| Into the Interior |

|---|

| Rainy Pass to Rohn 48 mi (77 km) |

| Rohn to Nikolai 75 mi (121 km) |

| Nikolai to McGrath 54 mi (87 km) |

| McGrath to Takotna 18 mi (29 km) |

| Takotna to Ophir 25 mi (40 km) |

| Trails diverge |

From Rainy Pass, the route continues up the mountain, past the tree line to the divide of the Alaska Range, and then passes down into the Alaska Interior. The elevation of the pass is 3,200 feet (980 m), and some nearby peaks exceed 5,000 feet (1,500 m). The valley up the mountains is exposed to blizzards. In 1974, there were several cases of frostbite when the temperature dropped to −50 °F (−45.6 °C), and the 50-mile-per-hour (80 km/h) winds caused the wind chill to drop to −130 °F (−90.0 °C). The wind also erases the trail and markers, making the path hard to follow. In 1976, retired colonel Norman Vaughan, who drove a dog team in Richard E. Byrd's 1928 expedition to the South Pole and competed in the only Olympic sled dog race, became lost for five days after leaving Rainy Pass, and nearly died.

The trail down Dalzell Gorge from the divide is regarded as the worst stretch of the trail. Steep and twisting, it drops 1,000 feet (300 m) in elevation in just 5 miles (8.0 km), and there is little traction so the teams are hard to control. Mushers have to ride the brake most of the way down, and use a snow hook for traction. In 1988, rookie Peryll Kyzer fell through an ice bridge into a creek, and spent the night wet. The route then follows Tatina River, which is also hazardous: in 1986 Butcher's lead dogs fell through the ice, but landed on a second layer of ice instead of falling into the river. In 1997, Ramey Smyth lost the end of his pinkie when it hit an overhanging branch while negotiating the gorge.

Rohn is the next checkpoint, and is located in a spruce forest with no wind and a poor airstrip. The isolation, and its location immediately after the rigors of Rainy Pass, and before the 75-mile (121 km) haul to the next checkpoint, makes it a popular place for mushers to take their mandatory 24-hour stop. From Rohn, the trail follows the south fork of the Kuskokwim River, where freezing water running over a layer of ice (overflow) is a hazard. In 1975, Vaughan was hospitalized for frostbite after running through an overflow. In 1973, Terry Miller and his team were almost drawn into a hole in the river by the powerful current in an overflow, but were rescued by Tom Mercer who came back to save them.

About 45 miles (72 km) from Rohn, the path leaves the river and passes into the Farewell Burn. In 1976, a wildfire turned 360,000 acres (1,500 km2) of spruce into blackened badland of burnt timber. Fallen trees, and falling through clumps of sedge or grass which balloon out into a canopy 2 feet (610 mm) above the ground, supporting a deceptively thin crust of snow, are common dangers. The Burn forces teams to move very slowly, and can cause paw injuries.

Nikolai, an Athabaskan settlement on the banks of the Kuskokwim River, is the first Native American village used as a checkpoint, and the arrival of the sled teams is one of the largest social events of the year. The route then follows the south fork of the Kuskokwim to the former mining town of McGrath. According to the 2000 census, it has a population of 401, making it the largest checkpoint in the Interior. McGrath is also notable for being the first site in Alaska to receive mail by aircraft (in 1924), heralding the end of the sled dog era. It still has a good airfield, so journalists are common.

The next checkpoint is the ghost town of Takotna, which was a commercial hub during the gold rush. Ophir, named for the reputed source of King Solomon's gold by religious prospectors, is the next checkpoint. By this stage in the race, the front-runners are several days ahead of those in the back of the pack.

Divided path

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|

After Ophir, the trail diverges into a northern and a southern route, which rejoin at Kaltag. On even years, the northern route is used; on odd years the southern route is used. During the first few Iditarods there was only one trail, which followed the route of what is now the northern trail. In the late 1970s, the southern leg of the route was added to give the southern villages a chance to host the Iditarod, and also to allow the route to pass through the trail's namesake, the historical town of Iditarod. The two routes differ by less than 10 miles (16 km).

The northern route first passes through Cripple, which is 503 miles (810 km) from Anchorage, and 609 miles (980 km) from Nome (ITC, Northern), making it the middlemost checkpoint. From Cripple, the route passes through Sulatna Crossing to Ruby, on the Yukon River. Ruby is another former gold rush town which became an Athabaskan village.

The southern route first passes through the ghost town of Iditarod, which is the alternate halfway mark, at 599 miles (964 km) from Anchorage, and 532 miles (856 km) from Nome (ITC, Southern). From Iditarod the route goes through the Athabaskan villages of Shageluk, Anvik, Grayling, and Eagle Island.

Ruby and Anvik are on the longest river in Alaska, the Yukon, which is swept by strong winds which can wipe out the trail and drop the windchill below −100 °F (−73.3 °C). A greater hazard is the uniformity of this long stretch: Suffering from sleep deprivation, many mushers report hallucinations (Sherwonit, 1991).

Both trails meet again in Kaltag, which for hundreds of years has been a gateway between the Athabaskan villages in the Interior, and the Inuit settlements on the coast of the Bering Sea. The "Kaltag Portage" runs through a 1,000-foot (300 m) pass down to the Inuit town of Unalakleet, on the shore of the Bering Sea.

Last dash

In the early years of the Iditarod, the last stretch along the shores of the Norton Sound of the Bering Sea to Nome was a slow, easy trip. Now that the race is more competitive, the last stretch has become one long dash to the finish.

According to the 2000 census, the village of Unalakleet has a population of 747, making it the largest Native American town along the Iditarod. The majority of the residents are Inupiat, the Inuit people of the Bering Strait region. The town's name means the "place where the east wind blows", and the buildings are commonly buried under snowdrifts. Racers are met by church bells or sirens, and mobbed by crowds.

From Unalakleet, the route passes through the hills to the Inupiat village of Shaktoolik, which is also buried in snow, after the northeast wind brings ground blizzards. The route then passes across the frozen Norton Bay, where the markers are young spruce trees that were dropped into holes in the ice, where they froze, to Koyuk. After the Bay, the route swings west along the south shore of Seward Peninsula though the tiny villages of Elim, Golovin and White Mountain.

All teams must rest their dogs for at least eight hours at White Mountain, before the final sprint. From White Mountain to Safety is 77 miles (124 km), and from Safety to Nome is just 22 miles (35 km). The last leg is crucial because the lead teams are often within a few hours of each other at this point. As of 1991[update], the race has been decided by less than an hour seven different times, less than five minutes three times, and in the closest race the winner and the runner-up were only one second apart.

The official finish line is the Red "Fox" Olson Trail Monument, more commonly known as the "burled arch", in Nome. The original burled arch lasted from 1975, until it was destroyed by dry rot and years of inclement weather in 2001. The new arch is a spruce log with two distinct burls, similar but not identical to the old arch. While the old arch spelled out "End of the Iditarod Dog Race", the new arch has an additional word: "End of the Iditarod Sled Dog Race".

A "Widow's Lamp" is lit and remains hanging on the arch until the last competitor crosses the finish line. The tradition is based on the kerosene lamp lit and hung outside a roadhouse, when a musher carrying goods or mail was en route. For this reason, the last musher to complete the Iditarod is referred to as the "Red Lantern".

On the way to the arch, each musher passes down Front Street, and down the fenced-off 50-yard (46 m) end stretch. The city's fire siren is sounded as each musher hits the 2-mile mark before the finish line. While the winner of the first race in 1973 completed the competition in just over 20 days, preparation of the trail in advance of the dog sled teams and improvements in dog training have dropped the winning time to under 10 days in every race since 1996.

An awards banquet is held the Sunday after the winner's arrival. Brass belt buckles and special patches are given to everyone who completes the race.

Mushers

More than 50 mushers enter each year. Most are from rural South Central Alaska, the Interior, and the "Bush"; few are urban, and only a small percentage are from the Lower 48, Canada, or overseas. Some are professionals who make their living by selling dogs, running sled dog tours, giving mushing instruction, and speaking about their Iditarod experiences. Others make money from Iditarod-related advertising contracts or book deals. Some are amateurs who make their living hunting, fishing, trapping, gardening, or with seasonal jobs, though lawyers, surgeons, airline pilots, veterinarians, biologists, and CEOs have competed. Per rules#1 and #2, only experienced mushers are allowed to compete in the Iditarod. Mushers are required to participate in three smaller races in order to qualify for the Iditarod. However, they are allowed to lease dogs to participate in the Iditarod and are not required to take written exams to determine their knowledge of mushing, the dogs they race or canine first aid. If a musher has been convicted of a charge of animal neglect, or if the Iditarod Trail Committee determines the musher is unfit, they are not allowed to compete. The Iditarod Trail Committee once disqualified musher Jerry Riley for alleged dog abuse and Rick Swenson after one of his dogs expired after running through overflow. The Iditarod later reinstated both men and allowed them to race. Rick Swenson is now on the Iditarod's board of directors. Rookie mushers must pre-qualify by finishing an assortment of qualifying races first. As of 2006[update], the combined cost of the entry fee, dog maintenance, and transportation was estimated by one musher at between USD $20,000 to $30,000.[5] But that figure varies depending upon how many dogs a musher has, what the musher feeds the dogs and how much is spent on housing and handlers. Expenses faced by modern teams include lightweight gear including thousands of booties and quick-change runners, special high-energy dog foods, veterinary care, and breeding costs. According to Athabaskan musher Ken Chase, "the big expenses [for rural Alaskans] are the freight and having to buy dog food". (Hutchinson) Most modern teams cost $10,000 to $40,000, and the top 10 spend between $80,000 and $100,000 a year. The top finisher won at least $69,000, the remaining top thirty finishers won an average of $26,500 each.[6] Mushers make money from their sponsorships, speaking fees, advertising contracts and book deals.

Dogs

The original sled dogs were Alaskan malamutes bred from wolves by the Mahlemuit tribe, and are one of the earliest domesticated breeds known. They were soon crossbred with Alaskan huskies, hounds, setters, spaniels, German shepherds, and wolves. As demand for dogs skyrocketed, a black market formed at the end of the 19th century, which funneled large dogs of any breed to the gold rush. Siberian huskies were introduced in the early 20th century and became the most popular racing breed during the AAS. The original dogs were chosen for strength and stamina, but modern racing dogs are all mixed-breed huskies bred for speed, tough feet, endurance, good attitude, and most importantly the desire to run. Dogs bred for marathon races weigh from 45 to 55 pounds (20–25 kg), and those bred for sprinting weigh 5 to 10 pounds (2.3–4.5 kg) less, but the best competitors of both types are interchangeable.

The huskies are a northern breed that prefer weather below freezing and above −50 °F (−45.6 °C). They sleep with their tail curled over their nose, which provides extra insulation once they are buried in snow.

Starting in 1974, all dogs are examined by veterinarians before the start of the race, who check teeth, eyes, tonsils, heart, lungs, joints, and feet; and look for signs of illegal drugs, improperly healed wounds, and pregnancy. All dogs are identified and tracked by microchip implants and collar tags. On the trails, volunteer veterinarians examine each dog's heart, hydration, appetite, attitude, weight, lungs, and joints at all of the checkpoints, and look for signs of foot and shoulder injuries, respiration problems, dehydration, diarrhea, and exhaustion. When mushers race through checkpoints the dogs do not get physical exams. Mushers are not allowed to administer drugs that mask the signs of injury, including stimulants, muscle relaxants, sedatives, anti-inflammatories, and anabolic steroids. As of 2005[update], the Iditarod claims that no musher has been banned for giving drugs to dogs.[7] However the Iditarod never reveals the results of tests on the dogs.

Each team is composed of twelve to sixteen dogs, and no more may be added during the race. At least six dogs must be in harness when crossing the finish line in Nome. Mushers keep a veterinary diary on the trail, but are not required to have it signed by a veterinarian at each checkpoint. Dogs that become exhausted or injured may be carried in the sled's "basket" to the next "dog-drop" site, where they are transported by the volunteer Iditarod Air Force to the Hiland Mountain Correctional Center at Eagle River where they are taken care of by prison inmates until picked up by handlers or family members, or they are flown to Nome for transport home.

The dogs are well-conditioned athletes. Training starts in late summer or early fall, and intensifies between November and March; competitive teams run 2,000 miles (3,200 km) before the race. When there is no snow dog drivers train using wheeled carts or all-terrain vehicles set in neutral.[citation needed] An Alaskan husky in the Iditarod will burn about 11,000 calories each day; on a body-weight basis this rate of caloric burn is eight times that of a human Tour de France cyclist. Similarly the VO2 max (aerobic capacity) of a typical Iditarod dog is about 240 milligrams of oxygen per kilogram of body weight, which is about three times that of a human Olympic marathon runner.

Criticism from animal rights groups

Animal protection activists say that the Iditarod is not a commemoration of the 1925 serum delivery. The race was originally called the Iditarod Trail Seppala Memorial Race in honor of Leonhard Seppala. According to statements made by Dorothy Page, the media perpetuated the false notion that the race was established to honor the drivers and dogs who carried the serum. Animal protection activists also say that the Iditarod is dog abuse, and therefore it is not an adventure or a test of human perseverance. They are also critical of the race because dogs have died and been injured during the race. The practice of tethering dogs on short chains, which is commonly used by mushers in their kennels, at checkpoints and dog drops, is also criticized. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals spokesperson Jennifer O'Connor says, "We're totally opposed to the race for the cruelty issues associated with it". The ASPCA said, "General concerns arise whenever intense competition results in dogs being pushed beyond their endurance or capabilities," according to Vice President Stephen Zawistowski. Dr. Paula Kislak, President of the Association of Veterinarians for Animal Rights, who practices veterinary medicine in California, has been very critical of the care the dogs receive.

On May 18, 2007, the Iditarod Trail Committee Board of Directors announced that they had suspended Ramy Brooks for abusing his sled dogs. The suspension is for the 2008 and 2009 races, and following that Brooks would be on probation for 3 years.

Records and awards

Dick Wilmarth won the first race in the year 1973, in 20 days, 0 hours, 49 minutes, and 41 seconds. The fastest winning time is Martin Buser's 2002 finish, in 8 days, 22 hours, 46 minutes, and 2 seconds. The closest finish was the 1978 victory by Dick Mackey. The win is controversial, because while the nose of his lead dog crossed the finish line one second ahead of Rick Swenson's lead dog, Swenson's body crossed the finish line first.

The first musher to win four races was Rick Swenson, in 1982. In 1991 he became the only person to win five times, and the only musher to win the race in three different decades. Susan Butcher, Doug Swingley, Martin Buser and Jeff King are the only other four-time winners.

Mary Shields was the first woman to complete the race, in 1974. In 1985 Libby Riddles was the only musher to brave a blizzard, becoming the first woman to win the race. She was featured in Vogue, and named the Professional Sportswoman of the Year by the Women's Sports Foundation. Susan Butcher withdrew from the same race after two of her dogs were killed by a moose, but became the second woman to win the race the next year, and subsequently won three of the next four races. Butcher was the second musher to win four races, and the only musher to finish in either first or second place for five straight years.

Doug Swingley of Montana was the first non-Alaskan to win the race, in 1995. Mushers from 14 countries have competed in the Iditarod races, and in 1992 Martin Buser—Swiss, but a resident of Alaska since 1979—was the first foreigner to win the race. Buser became a naturalized U.S. citizen in a ceremony under the Burled Arch in Nome following the 2002 race. The Norwegian Robert Sørlie was the first foreigner not resident in the United States to win the race in 2003.

In 2007 Lance Mackey became the first musher to win both the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod in the same year; a feat he repeated in 2008. Mackey also joined his father and brother, Dick and Rick Mackey as an Iditarod champion. All three Mackeys raced with the bib number 13, and coincidentally all won their respective titles on their sixth try.

The "Golden Harness" is most frequently given to the lead dog or dogs of the winning team. However, it is decided by a vote of the mushers, and in 2008 was given to Babe, the lead dog of Ramey Smyth, the 3rd place finisher. Babe was almost 11 years old when she finished the race, and it was her ninth Iditarod. The "Rookie of the Year" award is given to the musher who places the best among those finishing their first Iditarod. A red lantern signifying perseverance is awarded to the last musher to cross the finish line. The size of the purse determines how many mushers receive cash prizes. The first place winner also receives a new pickup truck.

List of winners

| Year | Musher | Lead dog(s) | Time (h:min:s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Hotfoot | 20 days, 00:49:41 | |

| 1974 | Nugget | 20 days, 15:02:07 | |

| 1975 | Nugget & Digger | 14 days, 14:43:45 | |

| 1976 | Puppy & Sugar | 18 days, 22:58:17 | |

| 1977 | Andy & Old Buddy | 16 days, 16:27:13 | |

| 1978 | Skipper & Shrew | 14 days, 18:52:24 | |

| 1979 | Andy & Old Buddy | 15 days, 10:37:47 | |

| 1980 | Wilbur & Cora Gray | 14 days, 07:11:51 | |

| 1981 | Andy & Slick | 12 days, 08:45:02 | |

| 1982 | Andy | 16 days, 04:40:10 | |

| 1983 | Preacher & Jody | 12 days, 14:10:44 | |

| 1984 | Red & Bullet | 12 days, 15:07:33 | |

| 1985 | Axle & Dugan | 18 days, 00:20:17 | |

| 1986 | Granite & Mattie | 11 days, 15:06:00 | |

| 1987 | Granite & Mattie | 11 days, 02:05:13 | |

| 1988 | Granite & Tolstoi | 11 days, 11:41:40 | |

| 1989 | Rambo & Ferlin the Husky | 11 days, 05:24:34 | |

| 1990 | Sluggo & Lightning | 11 days, 01:53:23 | |

| 1991 | Goose | 12 days, 16:34:39 | |

| 1992 | Tyrone & D2 | 10 days, 19:17:15 | |

| 1993 | Herbie & Kitty | 10 days, 15:38:15 | |

| 1994 | D2 & Dave | 10 days, 13:05:39 | |

| 1995 | Vic & Elmer | 10 days, 13:02:39 | |

| 1996 | Jake & Booster | 9 days, 05:43:13 | |

| 1997 | Blondie & Fearless | 9 days, 08:30:45 | |

| 1998 | Red & Jenna | 9 days, 05:52:26 | |

| 1999 | Stormy, Cola & Elmer | 9 days, 14:31:07 | |

| 2000 | Stormy & Cola | 9 days, 00:58:06 | |

| 2001 | Stormy & Peppy | 9 days, 19:55:50 | |

| 2002 | Bronson | 8 days, 22:46:02 | |

| 2003 | Tipp | 9 days, 15:47:36 | |

| 2004 | Tread | 9 days, 12:20:22 | |

| 2005 | Sox & Blue | 9 days, 18:39:30 | |

| 2006 | Salem & Bronte | 9 days, 11:11:36 | |

| 2007 | Larry & Lippy | 9 days, 05:08:41 | |

| 2008 | Larry & Handsome | 9 days, 11:46:48 | |

| 2009 | Larry & Maple | 9 days, 21:38:46 |

Most wins

| Musher | Wins | Years |

|---|---|---|

| Rick Swenson | 5 | 1991, 1982, 1981, 1979, 1977 |

| Jeff King | 4 | 2006, 1998, 1996, 1993 |

| Martin Buser | 4 | 2002, 1997, 1994, 1992 |

| Doug Swingley | 4 | 2001, 2000, 1999, 1995 |

| Susan Butcher | 4 | 1990, 1988, 1987, 1986 |

| Lance Mackey | 3 | 2009, 2008, 2007 |

| Robert Sørlie | 2 | 2005, 2003 |